A HISTORY OF FRENCH COURSES: Roasts

This is the third post in a series on the history of French meal courses. The first was an overview of the subject. The second was a look at soups and pottages.

A 1948 menu from Chez Louis takes things a step further, offering only a “Plats” course which explicitly includes roast goose (but no steak of any sort, which may reflect post-war limitations).

Another menu from that year has a single heading for “Entrées-Roasts-Grillades”.

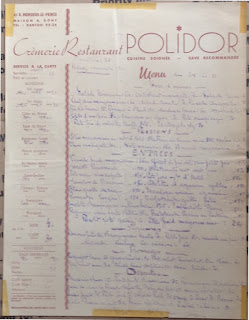

A 1951 menu from the venerable Polidor again has an entrées course (which includes roast chicken) but no roasts course.

A 1954 menu from Maxim’s offers entrées and grillades.

These tendencies continued in the post-war period. A 1972 menu again lists “plats” but no roast course.

The

idea that meat is the heart of a meal is encoded in the phrase: “the

meat of the matter”; that is, the one, central, essential

ingredient. It may come as no surprise that it has its roots in the

barbarian ancestry of Western culture. The Romans certainly ate meat,

and it was part of the principal course in a large, formal meal: the

coena. But fish, notably, played a larger part. Above all, the

principal course was characterized by variety, and so pork might be

served with poultry, as well as fish and shellfish. Meanwhile, both

the Greeks and the Romans commented, not entirely approvingly, of the

barbarians’ love of meat (“barbarian” here meaning mainly

Germanic groups, but also the pre-Roman Celts). For these groups, meat

WAS the heart of the meal.

The

Germanic Franks were firmly established as masters of Gaul by the

time we have the first account of a roast being a separate, and

important, course in a meal; this

from Charlemagne’s biographer: “His daily meal was served in four

courses only, exclusive of the roast, which the hunters used to bring

in on spits, and which he ate with more pleasure than any other

food.”

Centuries later, however, when

Philip the Bold wanted to regulate

meals in 1279, he only mentioned pottages of meat or fish, but no

roast (either as a course or a dish).

In a series of sample menus from the fourteenth

century Ménagier de Paris, the roast

is the only course to be named, along with the ordinal numbers which are all

that distinguish the other courses. In these cases, the roasts

resemble Roman practice in offering an assortment of foods, including

fish. By then too, French meals were divided (as was not true at the

start of the Middle Ages) into meat and meatless meals, and so one

sees references to “rost de char” (meat roast) (for meatless meals, the references are mainly to the "best one can"). But the

recipes in the same work are organized into several sections, one

including

roasts. The Viandier, which preceded it, included

a section on roasts.

In

regulating meals in 1563 Charles IX only referred to “meat

or fish” for the second course. But eleven years later,

criticizing luxury in meals, Bodin referred to an “ordinary”

meal of boiled, then roasted food, then “fruit” (dessert).

(He then went on to bitterly complain about the embellishments which

were added to these in practice.)

In

1655, Bonnefons still referred to courses by numerical order, but the

last was to be made up of “roast

birds and game, on the dishes, the small roast, and so on.” And

so one sees the roast fitfully being singled out at this point. By

1693, the anonymous author of L’art de bien traiter refers

to a sequence of “pottages,

entrées, roast meats, salads and entremets”.

As

meals expanded at the higher reaches of Society, a meal could include

a growing number of courses, but one was always of roasts. When the

Marshal of Bouffiers gave a feast in 1698, it began with pottages (or soups) and hors d’oeuvres, followed by entrées, then roasts (here all birds of various sorts). This was still

relatively restrained; the roast was followed only by entremets and

fruit (dessert).

But

in 1757, a meal for Louis XV began with four different courses

before “Two

Moderate Roasts” (actually roasts of eight different birds).

Only an entremets course followed this, but of numerous dishes,

including many we would today consider dessert. In a grand meal like

this, then, the roast course was the high point of a meal, but easily

lost in a series of other courses.

Things

were little better with the menus of the first great restaurants.

Beauvilliers’, for instance, one of the most famous at the start of

the century, did indeed offer a roast

course towards the end of its offerings. But this was preceded by

soup, hors d’oeuvre and (savory) pastry courses, before several

entrée options, one of which was already made up of beef dishes.

Presumably no one diner had ALL these courses, and the roast probably

still held pride of place in many meals, but it does not necessarily

stand out in these extended early menus.

Working

class eateries made meat the heart of many meals, but it was often

boiled

beef.

In

the latter part of the century, one common option was a Bouillon

– basically, the first chain restaurants, with limited but cheap

options. A menu for one of these shows “Plats du Jour” which

include some meat dishes, but also a separate heading for “Roasts”,

including beef, veal and lamb options.

In 1886, Van Gogh ate at another, in which the long list of entrées included various meat options, including roast beef, but a separate Roasts course simply included chicken with cress (once a common side) and veal or roast beef as alternatives.

Exceptionally, an 1895 menu from the Taverne de l’Opera combines these as an “Entrées and Roasts” course.

What one starts to see here is the appearance of more and more meat dishes offered as entrées even as the separate roasts course persisted, along with the original Germanic idea that a meal had to include meat to be a proper meal.

[Click on each image to see larger view]

In 1886, Van Gogh ate at another, in which the long list of entrées included various meat options, including roast beef, but a separate Roasts course simply included chicken with cress (once a common side) and veal or roast beef as alternatives.

Exceptionally, an 1895 menu from the Taverne de l’Opera combines these as an “Entrées and Roasts” course.

What one starts to see here is the appearance of more and more meat dishes offered as entrées even as the separate roasts course persisted, along with the original Germanic idea that a meal had to include meat to be a proper meal.

This

tendency continued into the twentieth century. A 1906 menu for the

famous Café

de Paris lists two kinds of steak under its entrées,

but only birds and lamb under its roasts.

Rather then than the old roasts category disappearing, it began to be divided between the entrées and the roast courses, sometimes on no better pretense, apparently, than that a steak was served with a sauce or a special side (thus taking it out of the simple roasts category).

Rather then than the old roasts category disappearing, it began to be divided between the entrées and the roast courses, sometimes on no better pretense, apparently, than that a steak was served with a sauce or a special side (thus taking it out of the simple roasts category).

Proceeding

through the twentieth century, one sees not only the slow

disappearance of the roasts course (though certainly not of meat),

but shifts in categories which become less fixed with time.

A

1906 menu from another Bouillon takes a mixed approach, offering a

combined heading of “Entrées Rotis”.

But a 1917 menu for the Bouillon Chartier on the Rue Racine (today reopened as the Bouillon Racine) offers only a two line entrées course.

Another menu from the Café de Paris, this from 1924, lists no headings at all, just grouping meats after fish.

Another menu from 1924, from the Mirabeau, lists entrées and roasts, along with a new category: grillades (grilled meats), effectively a substitute for roasts.

A 1930 menu from Le Commerce (which may or may not be related to a surviving place at a different address) offers plats du jour, entrées and again grillades. Why some meat is in the first category and some in the second is not at all clear. Veal kidneys flambés appear in the first, tripe with muscadet in the second, even though both are offal with alcohol.

Otherwise, the increasing dominance of the grillades category acknowledges a long-standing change, which is that much meat which was formerly roasted had, for some time, been more likely to be grilled, if only because more and more of it was in some form of cut (like a steak) as opposed to being whole (like a chicken). Quite fortuitously this represents a return to the Roman practice of using a grill for much cookery, as opposed to the Germanic spit. But it is unlikely any of the practitioners involved were aware of that history.

But a 1917 menu for the Bouillon Chartier on the Rue Racine (today reopened as the Bouillon Racine) offers only a two line entrées course.

Another menu from the Café de Paris, this from 1924, lists no headings at all, just grouping meats after fish.

Another menu from 1924, from the Mirabeau, lists entrées and roasts, along with a new category: grillades (grilled meats), effectively a substitute for roasts.

A 1930 menu from Le Commerce (which may or may not be related to a surviving place at a different address) offers plats du jour, entrées and again grillades. Why some meat is in the first category and some in the second is not at all clear. Veal kidneys flambés appear in the first, tripe with muscadet in the second, even though both are offal with alcohol.

Otherwise, the increasing dominance of the grillades category acknowledges a long-standing change, which is that much meat which was formerly roasted had, for some time, been more likely to be grilled, if only because more and more of it was in some form of cut (like a steak) as opposed to being whole (like a chicken). Quite fortuitously this represents a return to the Roman practice of using a grill for much cookery, as opposed to the Germanic spit. But it is unlikely any of the practitioners involved were aware of that history.

A

prix fixe offering from 1939 offers two options with entrée courses,

followed by a choice of roasts (some with sides).

In the 1940’s the Rocher de Cancale, already a far more modest restaurant than in its nineteenth century heyday, offered two different, but increasingly common, headings: “Plats du Jour” (now often, in practice, the entrées) and “Grillades”. In this case, their Chateaubriant comes with Pommes Soufflées, an addition which would have pushed it into the entrées on some other menus.

In the 1940’s the Rocher de Cancale, already a far more modest restaurant than in its nineteenth century heyday, offered two different, but increasingly common, headings: “Plats du Jour” (now often, in practice, the entrées) and “Grillades”. In this case, their Chateaubriant comes with Pommes Soufflées, an addition which would have pushed it into the entrées on some other menus.

A 1948 menu from Chez Louis takes things a step further, offering only a “Plats” course which explicitly includes roast goose (but no steak of any sort, which may reflect post-war limitations).

Another menu from that year has a single heading for “Entrées-Roasts-Grillades”.

A 1951 menu from the venerable Polidor again has an entrées course (which includes roast chicken) but no roasts course.

A 1954 menu from Maxim’s offers entrées and grillades.

These tendencies continued in the post-war period. A 1972 menu again lists “plats” but no roast course.

Without

continuing into the subsequent variations through the end of the

century, it seems clear that the roasts course per se had essentially disappeared

by World War II. How much was this a matter of reality and now much a

matter of arbitrary categories? Certainly, the Germanic innovation of

considering meat central to a meal remained well-established in

French dining, and in that sense the original influence of the roast

still has not faded away, although vegetarianism and foreign

influences on French food have much diminished it. On the other hand,

the literal idea that meat not cooked in liquid was likely to be

roasted probably began to give way at the start of the nineteenth

century to the idea of grilling it. One still finds roasts on French

menus, but far fewer than, say, cuts of steak. The disappearance then

of the centuries-old roasts course may reflect a material evolution.

Comments

Post a Comment